Literature review volume 8: SYMPTOM MODIFICATION

Nov 21, 2019

Welcome back to the Shoulder Physio literature review. This month we are tackling the in vogue concept of symptom modification. We will delve into what it is, what form it takes in clinical practice, and whether it is relevant or even special. I will focus on symptom modification in relation to; 1) Shoulder symptom modification procedure, 2) W functional therapy, and 3) Mobilisation with movement.

This months review is inspired an by article written by Greg Lehman that was published in JOSPT (ref). I strongly encourage you to read it.

What is symptom modification (SM)?

SM aims to reduce pain and improve function via the modification of painful movement. The effectiveness of this intervention can be derived from both mechanical and psychological processes. The concept of SM underpins many of the seemingly disparate approaches in physical therapy today. In fact, it pretty much summarises my entire university training; identify painful movement, perform an intervention, reassess previously painful movement. However, my explanation for the mechanism of effect here has undergone a dramatic change over the past few years.

Why has SM taken off recently? A history lesson beckons.

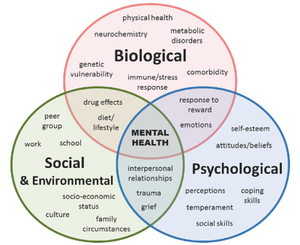

The last 10-20 years has seen the popularization of the biopsychosocial model. Whilst this is not a new model, first formulated by George Engel in 1977, it has been increasingly used as a model of reference for pain in MSK medicine due to distinct limitations of the biomedical model.

Western culture loves to fix things and we believe firmly in cause and effect (which is mostly a good thing – thanks to scientific revolution), however, in trying to explain complex phenomena (like pain) it barely scratches the surface. For the following medical conditions, this cause and effect model works very very well:

-

Infection = antibiotic

-

Hay-fever = antihistamine

-

Headache = aspirin

- Diabetes = insulin

-

Blocked sinus = decongestant

-

Fracture = fixation

-

Etc. etc.

In the above scenarios, the biomedical model of correcting organic pathology is a powerful antidote (antibiotics have saved millions of lives since their invention in 1927). I wholly respect these interventions, and I may not be sitting here writing this piece if it weren’t for their existence. However, in light of a barrage of new evidence (within the last 20 years) highlighting the importance of psychosocial factors in pain, we must evolve and incorporate this science into our everyday understanding of pain.

For pain, and particularly persistent pain, the biomedical model often falls woefully short. The following quotes from Professor Lorimer Moseley, accurately articulate this:

“The relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes weaker as pain persists”.

“The evidence that tissue pathology does not explain chronic pain is overwhelming”.

If we take low back pain as an example, a single pathoanatomic cause cannot be accurately identified in 90-95% of people with disabling LBP (O’Sullivan et al 2018). The same applies to the shoulder where it is now common (being very generous here) knowledge that structural abnormalities detected via imaging do not correlate with pain in a consistent manner (of course occasionally they do, but this is rarely the norm). Simply, patho-anatomy is but ONE input capable of contributing to the distressing experience of pain. In persistent pain, the general consensus is emotions, cognitions, behaviours and a bevvy of sociocultural factors may be more important than the visual observation of abnormal tissue morphology.

In physical therapy specifically, the biomedical model has seen us obsess about the following factors for decades:

-

Kinematics

-

Biomechanics

-

Motor control

-

Posture

- Structural integrity of tissue

-

Kinematics

-

Length of tissue

-

Neurodynamics

Although these physical factors DO MATTER they are not superior to the other dimensions of pain. In fact, in persistent pain, they may not matter at all! By focusing entirely on physical factors, we can worsen the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain, inadvertently. For example, "the bone spur in your shoulder is causing fraying of your rotator cuff tendons when you raise your arm". This biomechanical explanation can have catastrophic consequences for someone in pain, no matter how seemingly innocuous or benign it may sound to the therapist.

The utility of Symptom Modification

So how does SM fit into this new conceptualisation of pain and lack of evidence surrounding biomechanics and structure being a primary driver of non-traumatic MSK pain? SM might allow us to use biomechanical or physical interventions in order to update potential faulty beliefs about pain and our subsequent behaviours. In this scenario, the shoulder symptom modification procedure, cognitive functional therapy approach and mobilisations with movement may simply be using mechanical interventions in a safe context to update an individual's belief about pain.

Across the body, we know people exist with textbook "faulty biomechanics" and yet have no pain. We also know that interventions aimed at improving biomechanics can reduce pain but often the aberrant mechanics remain! Clearly, there must be something else going on here. SM may harness therapeutic movement, touch and education in a positive way to modify pain and allow an individual to re-conceptualise their pain or injury. This can be achieved without the true correction or restoration of postural or biomechanical norms.

Shoulder symptom modification procedure

First, let us consider the Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure (SSMP), which was created by Jeremy Lewis, PhD. The SSMP maps out several specific physical interventions/modifications to the:

- Scapula

- Thoracic spine

- Humeral head

After modifying the movement or input of the above structures we then monitor the symptom response. If pain is reduced or abolished, this is deemed a good thing and we try and do this particular movement in a home exercise program. But is the vital component of the procedure the kinematic modification or is it the fact symptoms CAN BE MODIFIED that powerfully communicates to the person in pain their symptoms can be reduced? This reduction or change in pain can lead to a de-threatening of movement and improved feelings of confidence and robustness, which are associated with improved outcomes. I see this all the time in the clinic, by modifying a movement (in a multitude of ways) we can change pain and as a result, reduce the threat associated with said movement. I am convinced it is not the kinematic change itself, but the internal response as a result of the modification.

Cognitive function therapy

Cognitive functional therapy (CFT) works in a very similar way. This approach has been popularised by Peter O'Sullivan and there is some reasonable evidence for its effectiveness, primarily in the lumbar spine.

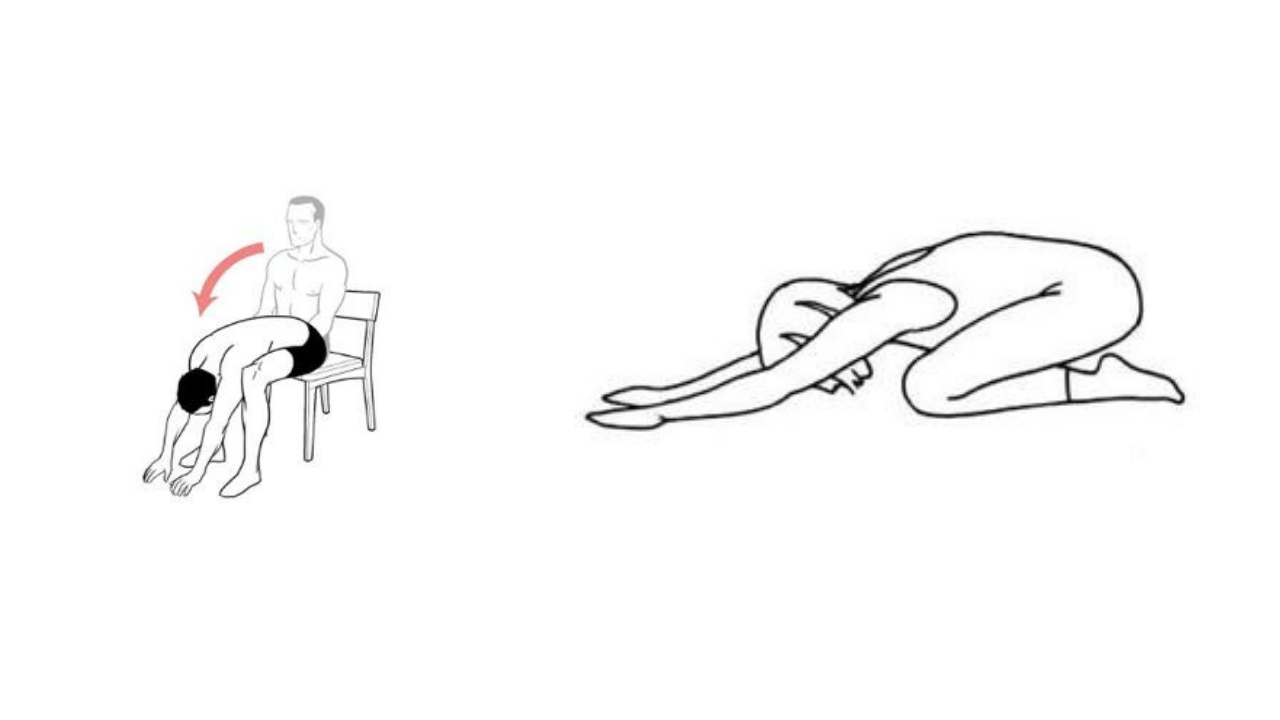

This model essentially involves education and identification of potential faulty or maladaptive beliefs about pain, followed by exposure with control (which is the symptom modification part) and finally education on healthy lifestyle factors. All very worthy components of health promotion. The part I’m interested in is the "exposure with control" step, which is basically progressively exposing people to painful movements in a safe way or with an altered context. For painful lumbar flexion in standing, this may be performing the flexion movement in short or long sitting or 4 point kneeling (see below). This could sufficiently change the context of the feared or sensitised movement and allow for the safe completion of a lumbar flexion movement without associated pain. So, if the spine is still flexing but there is less pain, it points to the cognitions and behaviours associated with said movement, not the absolute mechanics, which was perpetuating the pain. This is the beauty of the CFT model and why I use it routinely.

Mobilisation with movement (MWM)

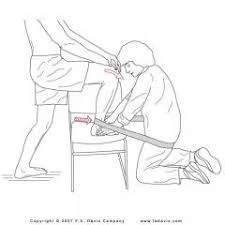

MWM's were a big component of my training at university. If not familiar, the concept of the MWM is the application of an accessory glide to a joint (often by the therapist) with a corresponding physiological joint movement, performed actively by the patient. See below for an illustration of the concept for improving ankle joint dorsiflexion. As far as joint mobilisation techniques go, the MWM model would have to be my personal favourite, really just because their is an active movement component. In terms of the mechanism of affect, I think it works exactly the same as the SSMP and CFT model; providing a mechanical input to change a painful movement. Again, I am comfortable in suggesting that the benefits here are derived from altering the context or perception of movement, as opposed to any meaningful change in joint mechanics.

Closing

The beauty of symptom modification is that it successfully acknowledges the stack of recent research which emphatically suggests emotions, cognitions and behaviours in response to pain are the primary predictors of long term outcomes NOT patho-anatomical or kinesiopathological factors. It also utilises physical therapists advanced knowledge of human movement and pain science in order to achieve this outcome, so I think it’s a win-win. Of course, there will be moments when it doesn’t work, especially in very acute cases of pain (when simple natural history will likely work) or when beliefs are so entrenched that they can’t be updated, but I think it is a great option for some people with persistent MSK pain.

The Complete Clinician

Tired of continuing education that treats clinicians like children who can’t think for themselves?

The Complete Clinician was built for those who want more.

It’s not another lecture library, it’s a problem-solving community for MSK professionals who want to reason better, think deeper, and translate evidence into practice.

Weekly research reviews, monthly PhD-level lectures, daily discussion, and structured learning modules to sharpen your clinical edge.

Join the clinicians who refuse to be average.