Manual therapy... the devil is in the context?

Sep 10, 2019

Manual therapy...

As I sit down to write this literature review, I admit, I have some trepidation. The topic of manual therapy (MT) in physical therapy, and pain management more broadly, can be a controversial discussion and shares many parallels with religion and politics. It's certainly a great way to ruin a dinner party! (yes, the dinner parties I attend are slightly strange). There are extreme views for and against this intervention, both with low-moderate evidence in support of each end of the spectrum. Both camps like to yell at each other and call each other names. I will attempt to provide a reasoned and moderate interpretation on the current state of play of manual therapy in physical therapy, and then relate it to the shoulder.****

Disclaimer: my bias leans heavily towards a minimalist hands-on approach. Exercise/movement and education are certainly the HEROES of my philosophy to managing pain and injury.

A history of thought... from bio to biopsychosocial to enactivism!

Throughout my near decade as a physiotherapist, I have been trying to navigate my way around manual therapy, both pragmatically and emotionally. You see, western medicine is firmly mired in a “cause and effect” model of healthcare. There needs to be an organic cause to pain or disease. Consequently, this organic pathology ultimately needs "fixing" if a cure is to emerge. In physical therapy, this began as tightness, weakness, stiffness, motor control impairments, and hypermobility etc. etc. This reductive biomedical model, which still prevails today in western culture, demanded these impairments be corrected, by strengthening, stretching, MANUAL THERAPY techniques, and motor control exercises, if dysfunction was to be eradicated! This message has been propagated in colleges, universities, national bodies, mainstream media and culture as a whole, and is now, I think, almost inextricably linked with physical therapy (in Australia at least). This, unfortunately, predicts some form of therapeutic manual therapy will be expected in a consultation with a physical therapist. Here lies the friction.

In the past 50 years there has been some push-back to this biomedical model of organic pathology = symptoms. Most notably, Engel (1977) developed the biopsychosocial model as a way of interpreting the inter-connectedness of pain and health using the trichotomy of biological, psychological, and social factors and their contribution to the human condition. This approach is not perfect, and has been criticised, but it was a giant leap forward. More recently, an enactive approach (borrowing heavily from phenomenology) to pain has been suggested. This model essentially proposes that humans are indistinguishable from their environment and biological, psychological, social, cultural, and evolutionary factors are all acting simultaneously to produce a complex, individual experience. Within this model, the in vogue “predictive processing” concept is also utilised. Predictive processing is something I am fascinated by and appears to be the future (as I see it) in explaining the experience of pain. The following quotes really resonate with me when trying to describe predictive processing:

“We perceive the world not as it actually is, but the brains best guess of it, continuously refined by incoming sensory evidence” Ongaro and Kaptchuk, 2019.

“We feel pain because we predict we are in pain, based on an integration of sensory inputs, prior experience, and contextual cues”. Ongaro and Kaptchuk, 2019.

Essentially, our brain/body develop a working hypothesis about the world, this includes pain. Our brain and body can be wrong, though, and persist with a hypothesis about our pain in the absence of any true pathology or disease. This explains “unexplained pain” elegantly. The job of the therapist is then “how do we update this person’s hypothesis about their environment and pain?” What interventions can we utilise to achieve this re-learning?

Moving onto manual therapy

What does MT include? I think the following all fall under the banner of MT (not a comprehensive list):

- Joint mobilisations (in their various forms)

- Manipulation

- Soft tissue therapy (massage and trigger point therapy)

- Dry needling

- Acupuncture

- Muscle energy techniques

What is the mechanism of action of manual therapy?

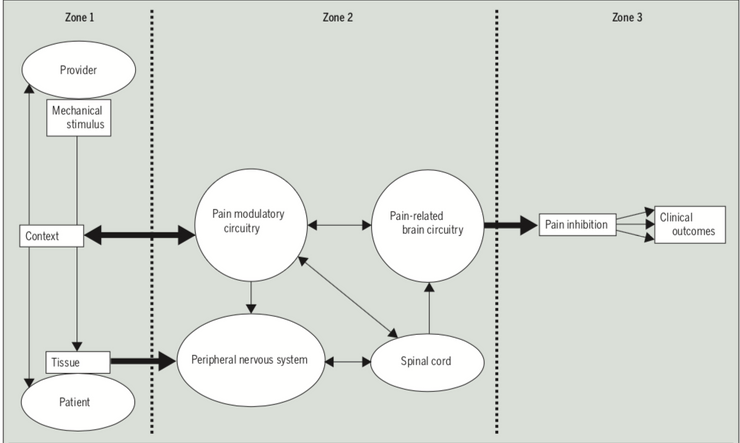

I am not going deep into this! Read these papers by Bialosky et al 2018 and “Placebo Mechanisms of Manual Therapy: A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing” by Bialosky et al 2017. The basic premise of the effect of manual therapy is a complex neurophysiological cascade of events that can result in pain inhibition. Secondly, there seems to be a powerful placebo mechanism in MT where context, beliefs, expectations and the ritual or ceremony of MT can result in perceived improvements in pain and function. The role of caring/supportive touch in physical therapy also needs to be mentioned. Therapeutic touch can provide feelings of safety and relaxation and reduce negative affective feelings, avoidance and stress related biomarkers (Tommaso et al 2019). This does not green-light manual therapy to be used needlessly or excessively. It merely provides a rationale behind its potential efficacy.

How does it fit into predictive processing? Potentially, the application of touch/MT to a threatening (painful) location of the body in a safe, supportive and sympathetic way may prompt the brain/body to update its hypothesis of the perceived affected area. In much the same way cognitive functional therapy or graded exposure works. At the end of the day, this is what we’re trying to do, right? Balance danger and safety signals (Danger in me Vs Safety in me in Lorimer Moseley and David Butler speak)? We are trying to minimise the danger and threat and promote feelings of safety. Especially in the case of persistent pain, where organic pathology does not align with symptoms and there may be a perception of threat/danger in the absence of any. Now I am not for a moment suggesting MT be trialed before graded exercise or cognitive functional therapy or that it is in any way superior to an active approach. Simply, the application of MT may actually work similarly and could be used in concert with the aforementioned approaches or if there are barriers to movement interventions in certain populations.

What does the evidence say? Exploring myths and misconceptions.

There has been a lot of talk about manual therapy reducing self-efficacy. I have scoured the literature looking for a reference to support this, but I simply cannot find one. I understand the theory behind the claim, but hypotheses need an experiment to confirm/reject the null, and at this stage this doesn't exist. Please send me a paper if you know of one, I would love to read it!! Intellectually, I do think that passive therapy MAY promote reliance on passive care and potentially take away self-efficacy BUT this has yet to be proven and I think if MT is delivered with the appropriate framing this concern may be allayed. It all comes back to education, and this is your job as a clinician!

Is manual therapy specific to the location it is applied? NO. Due to the central effects of MT, there may be a general analgesic response, often distal, to the site of application of MT (Bialosky et al 2018). You don't have to be exactly on L3 with your hands in a certain way, pushing in the right direction at the right magnitude to help someone! This complicated and over the top depiction of MT, which I'm sure most of us have suffered through, is what gives it such a bad name and we should rightly fight against this. It also may not matter what intervention you choose! Rub, mobilise, needle, it's likely all the same. As long as the context is conducive to a good response, the patient has a belief in the intervention and they expect some improvement out of it. A bit of grandstanding may help too ;)

Is there harm associated with manual therapy? Again, to my knowledge I am not aware of any studies that show harm comes from manual therapy. Of course, there are adverse events, especially with manipulation, as there is with other interventions, namely surgery, but when executed in a safe way, I’m not sure that manual therapy makes people worse. BUT does it actually make people better? This systematic review on MT in rotator cuff tendinopathy suggested MT used alone may significantly reduce pain, but may not improve function. I think this is a totally accurate finding. MT can reduce pain but probably doesn’t do much for function. This makes perfect sense to me. When a patient presents to me with shoulder pain, often they want a diagnosis, prognosis, a self-management strategy, pain relief and reassurance. Can manual therapy, either clinically by a physical therapist or at home using whatever tool they like, help with pain relief? Yes. Can it improve function/capacity and health related outcomes long term? NO! As such, for me, exercise and education come first, and will take up the lion share of my time in a consultation with a patient. If a patient wants some immediate symptomatic relief, have had good experiences in the past with MT, and do not exhibit any significant red flags and understand it is a short term neuro-modulatory intervention, will I consider MT? Yes, I will.

A recent systematic review on conservative interventions for subacromial impingement (kill me) found manual therapy was superior to placebo for pain and manual therapy + exercise was superior to exercise alone BUT only at short follow-ups. Exercise, on the other hand, was beneficial for both pain and function and was recommended as the primary intervention.

There is also evidence that adding manual therapy to exercise is not superior to exercise alone for pain, function and scapular kinematics (Camargo et al 2015). In fact, in this study, exercise alone trended towards greater improvements than manual therapy alone + exercise. Some food for thought. Although, as always, there are studies that show exercise + MT is superior to exercise alone (ref,ref)

Could time spent performing MT be better used elsewhere?

The inevitable question. My answer to this is a resounding YES. Of course, the priorities of health care will always be reassurance, education, promoting pillars of health, and encouraging self-management. However, as a health care provider we have to be flexible in our approach to helping patients. Just as we encourage patients to be adaptable in managing their pain (Dr. Bronnie Thompson has done a PhD on this!). If a particular intervention is wanted by a person who is suffering and there is no evidence of harm coming from this intervention, would you deny them this based on your own bias? I am not sure that we as physios have all the answers to everybody’s pain on earth, so I think we should take a step back, actually listen to the person in pain, apply the available evidence, and do our best to improve their quality of life with whatever tools we have available!

Are we walking placebo's?

Recently, there have been numerous studies that demonstrate the power of belief and expectation in pain and injury rehabilitation. Expectations are often the biggest predictor of outcome for those with many types of pain, this has been demonstrated in the shoulder too (ref). Even exercise can be a placebo, if you're told an exercise will help, it probably will! (ref) This has even been shown in placebo controlled surgical trials, which I have discussed previously (ref). Clearly, exercise has a myriad of other health benefits, and is literally the magic pill we all so desire and is far more than a placebo. However, just because one thing is probably better, does it make the other thing wrong? We should try and harness the positive placebo affects of MT, just as we do with all other interventions. NOT AT THE EXPENSE OF MOVEMENT!

Summary

In closing, manual therapy still stirs up emotional and passionate debate. I look at it very simply, it's neither the devil nor the saviour, it’s just another thing! I am a movement optimist and 99.99% of people I see will get a movement-based intervention and this will work far more often than not. However, I am open-minded enough to understand that people are complex individuals and their particular set of wants and needs may be different from the next person. I am very content to use whatever I can provide to reduce some suffering in an individual to facilitate their engagement in meaningful activities that will improve their quality of life. This is my moderate interpretation of the MT literature. Thanks for reading :)

Ready to gain the confidence to manage any shoulder pain patient who comes to see you?

My comprehensive course – developed over 10 years of treating shoulder patients and researching and educating professionals about shoulder joint function – covers all the above areas and more. In over 16 hours of training delivered in an engaging, self-paced, online format, you’ll learn everything you need to know to feel at ease treating people with shoulder pain.