The scapula and "the measurement problem"

May 18, 2020

Literature review, April 2020

There is a lot happening in the world right now but I will resist mentioning the "C" word as I'm sure you've all heard enough. So, instead of turning this literature review into a political commentary, I will stick to what I know best; shoulders!

This month I am taking on the mammoth task of the scapula - well a component of it anyway, specifically what I deem "the measurement problem". I am reviewing an article by Plummer et al 2017, titled:

Observational Scapular Dyskinesis: Known-Groups Validity in Patients With and Without Shoulder Pain (ref).

Background

Let's set the scene. This is a wonderfully elegant research design.

Essentially, the aims of the experiment were twofold:

-

Firstly, do clinicians display bias when determining whether a person has a scapula dyskinesis when there is KNOWN shoulder pain (unblinded examiner) Vs UNKNOWN shoulder pain (blinded examiner)

-

Secondly, do people without shoulder pain exhibit comparable levels of scapula dyskinesis compared to a population with shoulder pain?

Why do this study? Simple. We needed to determine if clinicians display confirmation bias when visually assessing the scapula of people with shoulder pain and whether this bias influences clinical decision making and treatment direction.

Confirmation bias "is a tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions, leading to statistical errors"

This study could be replicated to all motion observation (and palpation) testing in other joints of the body (if it hasn't already been done).

Okay, to the study

Participants: Included those with and without shoulder pain with various shoulder pathologies, excluding frozen shoulder, fracture, previous shoulder surgery, cervicogenic shoulder pain and systemic MSK disease.

Examiners: Consisted of blinded (unaware of the presence or absence of shoulder pain in subject) and unblinded (aware of the existence or absence of shoulder pain in subject)

Procedure: Utilised the SDT as described by McClure et al 2009 (ref)

135 participants enrolled in the study (67 with shoulder pain and 68 without).

Scapula dyskinesis test

This involves raising arms bilaterally with a small weight, or if can't be tolerated against gravity only, and the observer aims to determine the presence or absence of scapula dyskinesia using a 2 or 3 part classification system.

Results and discussion

-

Examiners who were "unblinded" reported higher prevalence rates of scapula dyskinesis Vs "blinded" examiner.

-

There were no significant differences between the shoulder pain group and the control group (without shoulder pain) in terms of the prevalence of scapula dyskinesis.

Interpretation

What to make of all this? Let me summarise in an economy of words: examiners in this study who KNEW the participant had shoulder pain were more likely to "see" a scapula movement issue.

Herein lies the intrinsic problem of motion assessment with our human senses. Our senses, while perfectly adequate for us to survive and prosper on earth, often deceive us and are prone to be perceived through a biased lens. Remember, vision is simply the stimulation of the retina by electromagnetic waves and is perhaps the most illusory of all senses. The brain is geared to see in a way that confirms its beliefs about how the world should look! (ref). So, if you believe scapula dyskinesis commonly contributes to shoulder pain, you may subconsciously and erroneously see something that isn't there.

The most applicable part of this study is its pragmatic nature of it. When people present to clinicians in real life looking for help, we are effectively unblinded and very much aware of the presence and location of the pain. Do we therefore apply our biased view of this pathology or clinical presentation to the person who presents to us, simply to confirm our view of the world? An example of this is after you attend a weekend workshop, on let's say, hip pain. You are far more likely to be paying extra attention to the hip on the Monday after the workshop and may find your diagnosis of FAI goes through the roof for the next few months. We see what we want to see, to confirm our beliefs of the world, often at the cost of true objectivity (if there is even such a thing in humans).

Predictive processing/coding would explain this as a fundamental human process that's related to our perception of the world and ourselves. This concept suggests and has empirical evidence for, that we actively try to minimise being wrong as much as we can in order to preserve our model of the world (ref). If we were wrong too often, our mind would descend into chaos and we wouldn't leave our bed in the morning! So we're not to blame, because this is how we successfully interact with the world. We just need to be aware of this when assessing people for movement discrepancies.

This finding is not limited to the scapula and should be applied to all assessment techniques where we use our senses (touch, vision etc.) to determine stiffness or aberrant movement patterns. I know you're thinking of many examples right now!

The next aim of this study was to determine if there was a difference in the prevalence of scapula dyskinesis between the control group and the shoulder pain group. The outcome was no significant difference between the two groups. Much like morphological change of biological tissue on imaging, movement patterns may vary from person to person and often don't need to be pathologised. Of course, there are exceptions to this, such as a nerve palsy or an unstable glenohumeral joint, but for rotator cuff related shoulder pain, I'm not sure it matters. The prevalence of scapula dyskinesis in people without shoulder pain has been reported to be as high as 72% (ref) and this paper suggested 62% of people without shoulders were deemed to have a scapula dyskinesis. This begs the question, how relevant is a scapula dyskinesis when many asymptomatic people exhibit this phenomena? Maybe it has a predictive value? (another discussion).

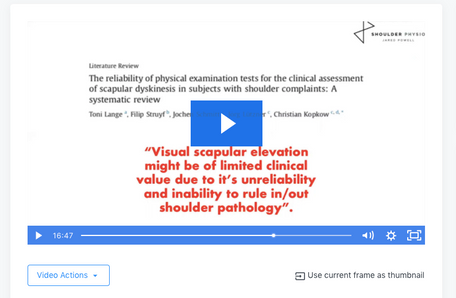

This is not to mention the diagnostic accuracy of scapula assessment and whether it adds any additional information to a shoulder physical examination. In fact, Wright et al 2013, went as far as to say "scapula asymmetry or motion alterations do not provide any additional clinical examination benefit with regard to diagnosing shoulder pain or pathology" (ref). Bold statement, but the evidence supports this. There does not appear to be much utility in scapula assessment for RCRSP as it provides very little help in diagnosis.

It is not possible, based on the current literature, to establish causation in the relationship between scapula dyskinesis and pain. In fact, the association, if it exists at all, is quite nebulous (ref). Scapula dyskinesis may simply be a victim at the scene of the crime or it may actually be trying to "save" the shoulder as a result of rotator cuff weakness?!

Closing thoughts

The scapula and its assessment is culturally and professionally ubiquitous for ALL MSK clinicians and is taught in 100% of all programs around the world (no evidence for this wild statement but I am willing to bet on it). However, it seems there is a fundamental "measurement problem" associated with the examination of the scapula. Clinicians may demonstrate confirmation bias when assessing the scapula in people with known shoulder pain, which will affect the objectivity and accuracy of a visual assessment technique. This bias will then inflate the detection of a dyskinesis, altering the trajectory of PT intervention. This may lead down the path of complicated scapula stabilisation exercises, nocebic and fear-inducing terminology (you can't go back to sport until your scapula is moving "properly"), and a focus on manual correction of scapula position via manual therapy or taping. So, the assessment of scapula movement appears riddled with biases, statistical errors and a lack of diagnostic accuracy. Consider this next time you assess a shoulder.

Thanks for reading :)

For a deeper analysis of the scapula and it's relationship with shoulder pain and pathology, check out my online course HERE

Ready to gain the confidence to manage any shoulder pain patient who comes to see you?

My comprehensive course – developed over 10 years of treating shoulder patients and researching and educating professionals about shoulder joint function – covers all the above areas and more. In over 16 hours of training delivered in an engaging, self-paced, online format, you’ll learn everything you need to know to feel at ease treating people with shoulder pain.